If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve heard the statistics. Nationally, white families hold roughly 10 times the wealth of Black families. And one of the starkest indicators of that disparity is homeownership: just 44.1% of Black Americans own a home, compared to 72.3% of white Americans. In Pittsburgh, the gap is even wider, with only 31% of Black households owning homes.

You’ve likely also noticed the city’s vacancy crisis. Drive through Pittsburgh, and you’ll see the empty lots, the boarded-up houses, the slow erosion of once-thriving neighborhoods. As of 2022, Pittsburgh was home to around 55,000 vacant units.

While at face value these may seem like separate issues, they are actually deeply connected, and understanding how is key to creating meaningful change.

“It’s important that people make this connection,” shared Catapult Executive Director Tammy Thompson. “Because what is happening in our communities today is a direct result of what happened yesterday.”

At Catapult, addressing economic injustice is at the heart of our mission. We work on a personal level with individuals and families to build generational wealth through financial education, entrepreneurship, and homeownership. But we also recognize the importance of zooming out to tackle the big-picture, structural issues at play, because true change requires understanding — and reimagining — the systems that shape our present.

In this article, we will take a closer look at the history that led us to the wealth gap we are facing today, because only when we understand that journey can we chart the path toward something better.

How racial discrimination was institutionalized: a brief history of redlining

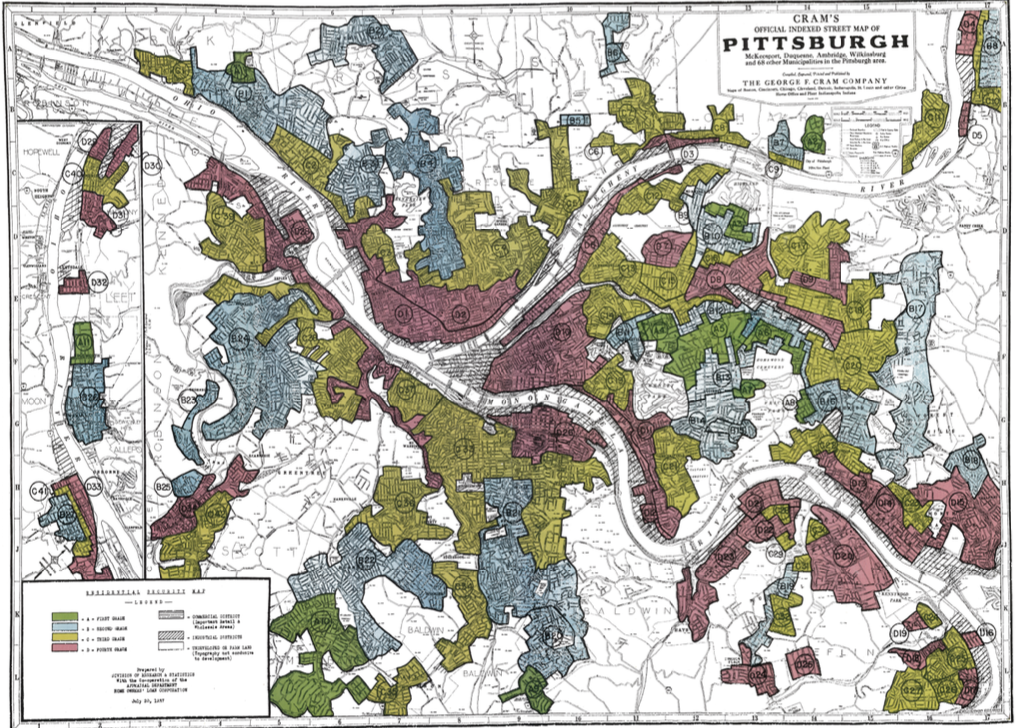

Our story starts back in the 1930s, when the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in an effort to stabilize the housing market — a pivotal moment that would go on to make racial discrimination a part of official housing policy. As part of its work, HOLC mapped cities across the country using a color-coded grading system to assess mortgage lending risk.

Neighborhoods shaded in green were rated the most favorable — typically all-white areas with no industrial presence or immigrant populations. In contrast, neighborhoods marked in red were labeled “hazardous.” These areas often had large Black and immigrant populations, older housing stock, and nearby industry.

As reported by PublicSource, in Pittsburgh, HOLC’s 1937 maps classified 11 neighborhoods as “best,” 27 as “still desirable,” 42 as “definitely declining,” and 34 as “hazardous.”

The impact of these maps was profound and far-reaching, effectively cutting off redlined areas from investment and home loans, resulting in disinvestment that spanned generations and can still be felt in communities across the nation, especially in Pittsburgh.

“If you take a redlining map from 50-60 years ago and superimpose it over the maps where all the neglected, rotted properties are, you’ll start to see the legacy of discrimination,” explained Shivam Mathur, real estate project manager at Main + Elm Development Company, a real estate development nonprofit in Pittsburgh.

Data from Pittsburgh’s Housing Needs Assessment backs this up. Communities that are home to some of the city’s largest concentrations of Black residents, like East Allegheny, Garfield, and Homewood, also contain some of the highest concentrations of housing in poor condition.

A living legacy of inequality

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was passed, which was the first major federal law to prohibit discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, color, religion, or national origin. While it targeted practices like redlining, enforcement was initially weak and discriminatory practices didn’t stop; they simply evolved.

One example is subprime lending that was rife in the 90s and early 2000s. Sometimes called “reverse redlining,” this practice targeted Black homebuyers and homeowners with high-interest loans. These loans often came with terms that made foreclosure far more likely, undermining the very protections the law was supposed to provide.

“This is why understanding history is so important,” explained Thompson. “We can’t keep saying, ‘Well, that was way back then,’ because the impact of those decisions is still happening. It’s not that people have been neglecting their communities, and as a result, there’s crime and blight — the roots of today’s challenges lie in deliberate decisions made at an institutional level decades ago.”

When we put all of this into the context of Pittsburgh’s post-industrial population decline — from almost 700,000 people in the 1950s to just over 300,000 people today — it’s clear to see how vacancy hit redlined neighborhoods harder.

“Anyone from those disinvested neighborhoods with financial mobility took their families to the inner ring suburbs or further outside of the city, leaving behind those with fewer options to endure worsening housing conditions — often until the homes became uninhabitable and they had no choice but to leave,” explained Main+ Elm Executive Director Jonathan Huck.

For the residents who stuck around or moved in later, all of this vacancy and blight is more than just an eyesore or a pain to live with. As Thompson points out, it’s also stealing people’s generational wealth.

“If you have communities full of vacancy and blight, they’re not going to increase in value, and so now homeowners in these communities will never see a return on their investment,” she noted.

Housing justice at scale

At Catapult, we are on a mission to repair this systemic harm affecting individuals across Pittsburgh and beyond, but to make a real dent in these issues, we can’t do it alone — and we need to address the scale of the problem.

“We can’t solve this by fixing up five or 10 houses. If we’re talking about really helping people create wealth, it’s gotta be entire blocks,” Thompson emphasized.

Through policy advocacy and collaborative partnerships, we are building momentum for solutions that engage government, community groups, and local residents alike to drive neighborhood-wide change.

Catapult’s CLEAR (Clinic for Legal Equity and Repairs) program, fueled by a generous $3 million investment from JPMorgan Chase, is one example.

Rising Tide helps CLEAR participants improve other houses on their block that are lowering property values.

“Ultimately, we’re helping families address problem properties around them, and from there, build solutions for their blocks and beyond,” Pelling explained.

In this scenario, real estate is a tool for solving everyday problems while also taking steps towards healing a long history of injustice. It’s a vision we hope to spearhead by getting people to dig deeper into the stories behind the statistics and work together as partners and collaborators.

“There’s an urgency to the problem that I think is important for the city to start addressing,” said Thompson. “We all know the statistics, but when are we going to talk about how we got here and what it’s going to take to get us out of here? That is the conversation I want to have, and it’s the conversation Catapult is helping to lead — not just by acknowledging the past, but by working every day to build a more just future.”